I finished reading a fine new book while on the road. It's Richard Slotkin's "Lost Battalions: The Great War and the Crisis of American Nationality," a worthy addition to the study of the racial, ethnic and social fault lines that are shot through American history.

In the aggregate, we Americans see our country as a multiracial and multicultural beacon. The reality is rather different. While I acknowledge that there have been huge gains in civil rights and that, yes, just about anyone who is white and male can grow up to be President of the United States, the great America melting pot has some pretty big holes.

The roots and genesis of this reality have long interested me, and "Lost Battalions" is a worthy companion to the seminal tract on the subject, Gary Gerstle's "American Crucible: Race and Nation in the Twentieth Century."

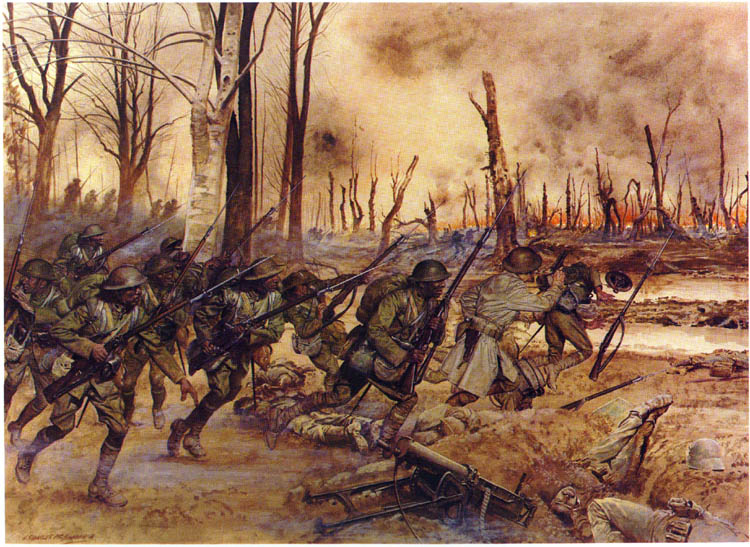

While Gerstle takes in the long sweep of the last 100 years in his 2002 study, Slotkin focuses on the World War I era and two combat units that he calls the Lost Battalions: the African-American troops of the 369th Infantry, who were known as the Harlem Hell Fighters, and the 77th Division, 0r Statue of Liberty Division, which was composed of New York City immigrants, most of them Jews.

Writes Slotkin:

The history of the Lost Battalions provides an answer to the question whether a "nation of nations" can maintain intself as a nation-state. In 1917 immigrants in every stage of assimilation from "fresh off the boat" to 100% Americanized, from Chinese deprived of families by the Exclusion Acts, to African-Americans subjected to the immiseration and humiliation of Jim Crow, all showed their willingness to serve the country in war and their desire to play a responsible role as political citizens in peace. It did not require ethnic homogeneity, cultural "amalgamation," or the imposition of a "one-language" standard for citizenship to make them effective patriots. To win their hearts and minds, their acceptance of the ultimate sacrifice, the nation had only to offer safety, a measure of dignity, a chance for material betterment, a credible promise of justice somewhere down the road, and a plausible claim that the war itself was just and necessary.That the U.S. did not keep its part of the bargain (some of the returning veterans were lynched and murdered) is tragic, but certainly not surprisingly. I urge you to read "Lost Battalions" to understand who we were then -- and why we are who we are today.

No more than that, and nothing less.

No comments:

Post a Comment