Osama bin

Laden is still dead. But beyond stating the obvious, virtually nothing that

the Obama administration has said about the run up to the assassination

of the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, the circumstances surrounding his

death and its immediate aftermath is accurate, according to a

fascinating but frustrating new exposé by Seymour Hersh.

"The Killing of Osama bin Laden" a 10,300-word takeout published in the London Review of Books

on Sunday, peels away layers of back-channel diplomatic intrigue only

hinted at in official pronouncements and news accounts about the May 2, 2011 climax to the massive international manhunt for world's most

wanted terrorist. In doing so, Hersh provides a fascinating

big-picture perspective filled with gritty detail, but he frustrates

because while some of his conclusions in making the argument

that "the White House's story [about bin Laden] might have been written

by Lewis Carroll" have the ring of truth, others seem far-fetched.

The

White House has dismissed Hersh's story as

_rdax_250x375.jpg)

"baseless," specifically his

assertion that the

administration collaborated with Pakistani officials. "The notion that

the operation that killed Osama bin Laden was anything but a unilateral

U.S. mission is patently

false," White House National Security spokesman Ned Price said in a

statement.

The much-lauded Hersh (photo, right) is the finest and one of the

most prolific investigative reporters of modern times, so anything under

his byline is worth taking seriously and this investigation certainly

is. Criticism of his heavy reliance on anonymous sources over the years has seemed like so many sour

grapes to this observer. That so noted, to its detriment the bin Laden story is very thinly sourced with Hersh's big and repeatedly cited go-to guy an unnamed but very well-connected "retired senior intelligence official" on which, it seems to me, he relies far too much with too little corroboration.

But

then it does seem to me that the man who broke the My Lai Massacre and Abu

Ghraib stories, among many other high-impact investigations, hasn't been

fully on his game for some time and isn't here. This may explain why The New Yorker,

where his exposés have appeared since 1993, is said to have taken a

pass on this one because it didn't hold up to the magazine's legendarily

tough scrutiny, while some observers assert that a British journalist

specializing in military intelligence broke key aspects of a story Hersh claims to be his own in

2011.

* * * * *

Hersh could not have chosen an investigative challenge with

a more complicated back story -- the deeply complex historic

relationship between the U.S. and Pakistan and their governments and

intelligence services, which has grown more complicated still since

President George W. Bush declared a global War on Terror following the

September 11, 2001, bin Laden-masterminded and Al Qaeda-implemented

attacks on the American homeland.

As

friends of America go, Pakistan has been the most two-faced and

duplicitous "ally" in that war. (Saudi Arabia is a close second.)

Pakistan has sucked up tens of billions of dollars in military and other

U.S. aid while coddling Al Qaeda and more recently the Taliban, and

providing a safe haven for bin Laden, who "was hiding in plain sight,"

as the White House put it, with several of his wives, other family

members and gofers in a walled and fortified compound in the resort town

of Abottabad, less than two miles the Pakistani version of West Point

and 40 miles from the capital of Islamabad. That is until it was expedient for the Pakistanis to sell out the terrorist leader.

Hersh

asserts that "the most blatant lie" perpetuated by the White House was

asserting that the U.S. went it alone in taking out bin Laden, whereas

what really happened was that the Pakistani intelligence

service captured bin Laden in 2006 and and brokered his fate to the U.S. in return for military aid and off-the-books favors to key Pakistani government players.

Hersh writes that Pakistan's two most senior

military leaders -- General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, chief of the army

staff, and General Ahmed

Shuja Pasha, director general of the Inter-Services Intelligence agency

(ISI)– were well in the loop on the clandestine Navy Seal-led mission

to take out bin Laden, who Hersh's source says had been held by the ISI

in the Abbotabad compound since 2006, with Saudi Arabia paying for the

upkeep of this exiled Saudi citizen, and had made sure that the two

Blackhawk helicopters

delivering the Seals to their target could cross Pakistani airspace

without being tracked or engaged.

Furthermore, Hersh writes,

"the CIA did not learn of bin Laden’s

whereabouts by tracking his couriers, as the White House has claimed . .

. but from a former senior Pakistani intelligence officer

who betrayed the secret in return for much of the $25 million reward

offered by the U.S."

Hersh writes that Asad Durrani, who was head of the ISI in the early 1990s, has told an Al-Jazeera interviewer that it was "quite possible" that senior

ISI officers did not know where bin Laden had been hiding, "but

it was more probable that they did [know]. And the idea was that, at the

right time, his location would be revealed. And the right time would

have been when you can get the necessary quid pro quo -- if you have

someone like Osama bin Laden, you are not going to simply hand him over

to the United States."

That

quid pro quo was reached, according to Hersh, at a time when the U.S.

was reducing the flow of U.S. aid in an effort to get the Pakistanis to

play ball on bin Laden, with an agreement between the Pentagon and its

Joint Special Operations Command and Pakistani bigs.

Under the

agreement, Hersh writes, Pakistan would play ball in return for the aid

tap being reopened and an understanding that news of the raid "shouldn't

be announced

straightaway. . . . the JSOC leadership believed, as did Kayani

and Pasha, that the killing of bin Laden would not be made public for as

long as seven days, maybe longer. Then a carefully constructed cover

story would be issued: Obama would announce that DNA analysis confirmed

that bin Laden had been killed in a drone raid in the Hindu Kush

[mountains], on

Afghanistan’s side of the border. The Americans who planned the mission

assured Kayani and Pasha that their co-operation would never be made

public. It was understood by all that if the Pakistani role became

known, there would be violent protests -- bin Laden was considered a

hero

by many Pakistanis -- and Pasha and Kayani and their families would be

in danger, and the Pakistani army publicly disgraced."

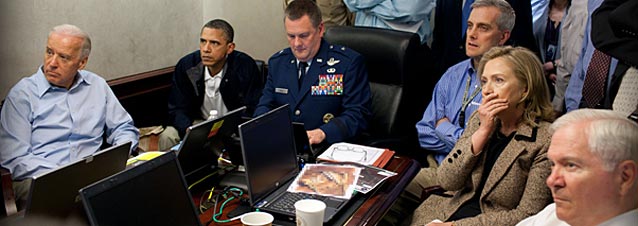

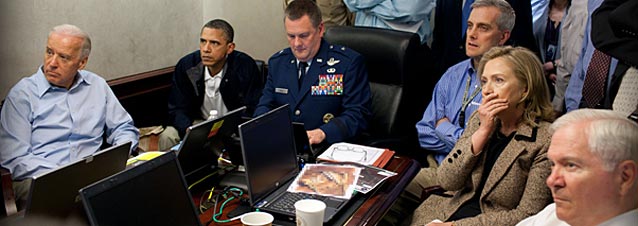

If

this deal is to be believed, then the U.S. betrayed the Pakistanis big

time as Obama, anxious to milk the biggest foreign success of his

presidency, a success that help insure his 2012 re-election, went public

with the news that bin Laden had been killed within hours of the

mission being completed. The decision to renege on the deal was made

when it was learned that one of the two Blackhawks had crashed at the

compound, a decision Hersh writes left Obama's top generals angry and

Defense Secretary Robert Gates apoplectic with rage.

Hersh writes

that because "the explosion and fireball would be impossible to hide,

and word of what

had happened was bound to leak, Obama had to get out in front of the

story before someone in the Pentagon did. Waiting would diminish the

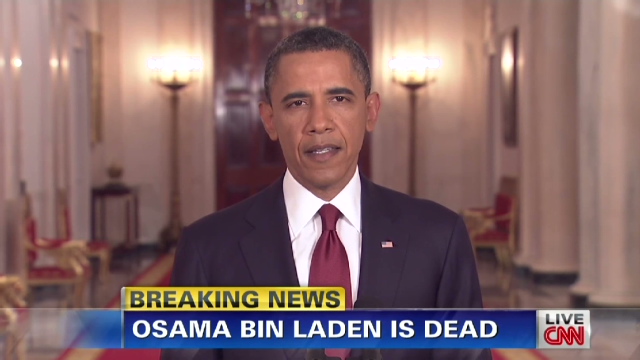

political impact. . . . Obama’s speech was put together in a rush and

was viewed by his advisers as a political document, not a message

that needed to be submitted for clearance to the national security

bureaucracy."

In what Hersh calls "political theater designed

to burnish Obama's military credentials . . . the self-serving and

inaccurate statements would

create chaos in the weeks following, including the assertion that

Pakistan had cooperated and the CIA's 'brilliant analysts' had unmasked a

courier

network handling bin Laden's continuing flow of operational orders to Al

Qaeda."

That statement, of course, risked exposing

Kayani and Pasha, so the White House's solution was to ignore what the president

had said and order anyone talking to the press to insist that the

Pakistanis had played no role in killing bin Laden.

"Obama left the clear

impression that he and his advisers hadn't known for sure that bin

Laden was in Abbottabad, but only had information about the

possibility," Hersh writes. "This led first to the story that the Seals had determined

they'd killed the right man by having a six-foot-tall Seal lie next to

the corpse for comparison (bin Laden was known to be six foot four); and

then to the claim that a DNA test had been performed on the corpse and

demonstrated conclusively that the Seals had killed bin Laden."

Hersh's

account begins to fray at this point because he

appears to be cherry picking aspects of the complex relationship between

U.S. and Pakistani intelligence to bolster his version of events, and I find it difficult to beieve his contention that the U.S. shared precise operational details of the raid with its Pakistani counterparts.

He

himself notes that Kayani and Pasha continued to insist they were

unaware of bin Laden's whereabouts as late as late autumn of 2010, or

about six months before the raid. I am skeptical that that was even

true of Kayani, who after all ran the Pakistani army, but it is

unbelievable in the case of Pasha. As head of the ISI, Pasha not only

would have known that bin Laden was being held under a kind of house

arrest by his own men, but that a former senior Pakistani

intelligence officer -- a "walk-in" in spy parlance -- had told the CIA

station chief in Islamabad in August 2010, as Hersh himself relates,

that bin Laden had lived undetected from

2001 to 2006 in the Hindu Kush, and that "the ISI got to him by paying

some of the local

tribal people to betray him."

The

other big lies told by the White House and CIA, at its behest,

according to Hersh, are the contention that bin Laden would have been

taken alive if he had immediately surrendered, that his body was flown

to Afghanistan and then disposed of at sea according to proper Islamic

religious custom, and that he remained in operational control of Al

Qaeda to the end.

The rules of engagement were that if bin Laden

put up any opposition

the Seals were authorized to take lethal action. But if they suspected

he

might have some means of opposition, like an explosive vest under his

robe, they could also kill him. "So here's this guy in a mystery robe

and

they shot him. It's not because he was reaching for a weapon. The rules

gave them absolute authority to kill the guy. The later White House

claim that only one or two bullets were fired into his head was

'bullshit,' the retired senior official said. The squad came through the

door

and obliterated him. As the Seals say, 'We kicked his ass and took his

gas.' "

Nevertheless, the fiction endures that the Seals had to

fight their way in, whereas the reality is that other than the Seals, no

shots were fired, according to Hersh.

He notes that only two Seals have spoken publicly: No Easy Day,

a first-hand account of the raid by Matt Bissonnette (photo, above left), was published in

September 2012, and two years later Rob O'Neill (photo, above right) was interviewed by Fox

News. Both had fired at bin Laden and both had resigned from the

Navy. "Their accounts contradicted each other on many details," Hersh

writes, "but their

stories generally supported the White House version, especially when it

came to the need to kill or be killed . . . O'Neill even told Fox News that he and his fellow Seals

thought 'We were going to die. The more we trained on it, the more we

realized . . . this is going to be a one-way mission.' "

Hersh

writes that in their initial debriefings, the Seals made no

mention of a firefight or any kind of opposition. "The drama and

danger portrayed by Bissonnette and O'Neill met a deep-seated need, the

retired official said: 'Seals cannot live with the fact that they killed bin Laden totally unopposed, and so there has to be an account of their

courage in the face of danger. The guys are going to sit around the bar

and say it was an easy day? That’s not going to happen.' "

(O'Neill told Fox News this week that he thought Hersh's account “was a joke . . . For someone who wasn’t there to say

stuff that I saw happen . . . it’s a comedy.” The former Seal took particular issue with Hersh’s allegation that there was no

firefight.)

According to the retired official, it wasn’t clear from the Seals' early

reports whether all of bin Laden’s body, or any of it, made it back to

Afghanistan, and the source asserts that "during

the helicopter flight back to Jalalabad [in Afghanistan] some body parts were tossed out

over the Hindu Kush mountains."

Obama stated in his hastily

arranged speech that Seals "took custody of his body," but Hersh notes

that statement created a problem since the initial plan was to announce

in a week or so that bin Laden was killed in a drone strike somewhere in

the mountains and that his remains had been identified

by DNA testing.

"Everyone now expected a body to be produced," Hersh writes. Instead, reporters

were told that bin Laden’s body had been flown by the Seals to an

American military airfield in Jalalabad . . . and then straight

to the USS Carl Vinson, a supercarrier on patrol in the

North Arabian Sea. Bin Laden had then been buried at sea, just hours

after his death.

The press corps's only skeptical moments at a

White House briefing led by CIA Director John Brennan later on the day

of Obama's speech had to do with the burial.

"The questions

were short, to the point, and rarely answered," Hersh writes. " 'When

was the decision

made that he would be buried at sea if killed?' 'Was this part of the

plan all along?' 'Can you just tell us why that was a good idea, John?'

'Did you consult a Muslim expert on that?' 'Is there a visual

recording

of this burial?' When this last question was asked, Jay Carney, Obama's

press secretary, came to Brennan's rescue: "We’ve got to give other

people a chance here."

Meanwhile,

the CIA asserted that a cache of valuable documents showing that bin

Laden was still running the Al Qaeda show was seized in the compound.

"These claims were fabrications: there wasn’t much activity for bin Laden

to exercise command and control over," Hersh writes. "The retired intelligence official

said that the CIA's internal reporting shows that since bin Laden moved

to Abbottabad in 2006 only a handful of terrorist attacks could be

linked to the remnants of bin Laden's Al Qaeda."

* * * * *

Hersh's exposés

are routinely criticized, typically a mix of indignity from officials

who feel they have been wronged and huffing and puffing from media mavens who can barely conceal their jealousy. That comes with the territory, but the bin Laden story blowback has been especially ferocious, which tells me Hersh is really onto something.

"The core problem with Seymour Hersh is that he relies entirely upon cranks [like the oft-quoted retired senior intelligence official] as his sources," writes one indignant maven, Slate's James Kirchick. "Cranks are an archetype of the intelligence

world. Imagine a cross between Connie Sachs (the reclusive, eccentric,

spinster Kremlinologist from John le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy) and Ron Paul, and you have an idea of the sort of person I’m talking about."

But look no further than Carlotta Gall (photo, above), who has covered Afghanistan and Pakistan for the New York Times for 12 years to validate the overall conclusion of Hersh's story because there is no other reporter more thoroughly versed on bin Laden's death. Kirchick, by comparison, is a babe in the woods.

"From the moment it was announced to the public, the tale of how Osama

bin Laden met his death in a Pakistani hill town in May 2011 has been a

changeable feast," Gall writes in corroborating Hersh's overall assertion regarding Pakistani involvement. "On this count, my own reporting tracks with Hersh's."

Gall does add that Hersh's claim that evidence

retrieved during the raid was less significant than has been asserted "rings less true to me. But he has raised

the need for more openness from the Obama administration about what was

found there."

Hersh himself brushed off the criticisms.

"If I worried about the reaction to what I write, I’d

be frozen," he said. Hersh said that journalists "should be very

skeptical of someone who says what goes against what every newspaper and

magazine believed. You're not doing your job if you say, 'Oh, it must be true.' "

My

own frustrations with the story aside, as well as concern over the thin sourcing, it does have one thing going

for it beyond Gall's endorsement and Hersh's own record of many more investigative hits than

misses: How the White House and the Washington press corps seem to be in

lockstep in agreeing that Hersh is a very naughty boy.

CNN National

Security Analyst Peter

Bergen's take rang especially hollow: "What's true in this story isn't

new, and what's

new in the story isn't true. I thought that was a pretty good way of

describing why no one here is particularly concerned about it."

Spoken like a true skepticism-free insider.

The Obama administration's obfuscations about the death of Osama bin Laden and the circumstances surrounding it seem minor compared to the massive cover-up of the 9/11 attacks and the circumstances surrounding that enormous event orchestrated by the Bush administration and a compliant Congress. Meanwhile, my thoughts on a 2009 Hersh story on whether Vice President Cheney had his own assassination squad.

_rdax_250x375.jpg)

ReplyDeleteI think Sy may just be a bit past it by now. Sourcing is a big part of it, as usual, but his rambling just doesn't even make sense to me. Most everything new he's reporting -- as well as, frankly, Carlotta Gall's "confirmation" of her bit of it -- is at least second-hand sourcing, or hearsay, in court-speak.

And the rest of it doesn't vary that much from the public accounting, though, like Benghazi, some of the factoids changed over the several days of disclosure. Why should that be so upsetting to journalists, knowing what we should about the first draft of history? Has the initial body count reported from either of the Nepal earthquakes been even close to correct?

If the "walk-in" dimed out the Pakis about bin Laden's presence as an ISI home-detainee, and his report was crucial enough for us to bring him & his kin Stateside for witness protection, why in hell do we then need to inform the Pakis that we're coming for bin Laden? And why, if they're so guilty of conspiring to trade bin Laden for some advantage like the aid money, what was the point if they were already getting the aid money, and weren't they later cut off from much of it? And why would one of their own risk life-and-limb to help lead a crew of Navy Seals inside bin Laden's house?

Then Ms. Gall cites a local Paki report about the walk-in to back up her own reporting, yet THAT reporter not only corroborates the walk-in story, but also cites the doc leading the the polio program. Hersh seems convoluted on that point, that I think he says the polio doc was an innocent humanitarian, doing good works and wrongly implicated by the US side in the bin Laden thing, while the real DNA culprit was this Paki Army major/doc who lived practically next door and was keeping bin Laden alive.

So Hersh, while using Gall as his own backup, is disputing the facts of the Paki journo whom she's using for backup. What a tangled web we weave.

I don't doubt the likelihood that the bin Laden takedown occurred differently than initially described, and that he likely was unarmed, or at least not fully capable of responding on his own -- and that the Seals didn't feel they needed any excuses (except publicly) to terminate with extreme prejudice. But nobody's going to own up to that for the record.

But I'd think it's extremely doubtful that the Seals would then decide on their own to dispose of the body piecemeal over the Hindu Kush, especially since it's likely the CIA would actually want to perform its own DNA test in an Afghan lab before getting rid of him.

I think the burial-at-sea may have been an afterthought, or maybe not, but being sure that none of his fans could make pilgrimages to any burial site to honor his martyred soul was likely crucial to everybody on the US side. So whether they actually dumped him in the sea or not, the U.S. side surely had no interest in disclosing precisely where his remains rested.

As for as the docs taken, I wouldn't have expected even as much as has been divulged publicly about the take they got there -- whether there was a lot or a little. But the fact that al-Qaida's No. 2, Mr. Zawahiri, acknowledged the provenance of what the US side had claimed would seem to give the lie to Hersh on that point, as Fisher notes.

I'm not sure in the whole Hersh piece, there's much there. Are you surprised that many details of a Special Op remain secret, or that some parts have cover stories? I'd have been more amazed, I guess, if Hersh maintained that we never got bin Laden.

Absolutely the best thing I've read on this subject.

ReplyDelete