With 29

million cars now having been recalled by General Motors for safety

problems -- which is substantially more than the 22 million recalled

last year by all automakers combined -- it is easy to conclude that GM

has learned little from its turbulent recent past, which has included

hemorrhaging market share for decades because of a crappy product line

and then a near-death bankruptcy averted by a taxpayer and labor union

bailout just as it was beginning to make attractive vehicles not

destined for rental-car fleets.

GM's

product line today -- from entry level compacts to behemoth pickup

trucks -- is as competitive as any vehicle manufacturer anywhere. Its

Cadillac brand is back from the dead and its overall fleet has been at

or near the top in initial J.D. Power quality ratings in recent years.

Several of GM's most venerable brands have been put out to pasture, and

with the company concentrating on fewer product lines its future looked

bright and Mary Barra, the first woman to head a major global automaker,

seemed like the right person for the job.

Until

its past began catching up to it in an extraordinary series of recalls,

many of which were for safety issues that came to the attention of GM

years ago but it failed to address head on.

* * * * *

I trace the beginning of General Motors’ downturn back to

1976 when a peppy little import called the Honda Accord first arrived in

the U.S. The 1976 Accord had just everything that the GM cars of that era didn’t. It was attractive, albeit in a cute sort of way. It was larger on the inside than it appeared from the outside, not the other way around. It had a rear hatch that opened to a collapsible back seat, offering lots of storage space. It handled well, had oomph and was economical, which was no small thing arriving as it did between the twin 1970s oil crises. A practical friend who had owned GM cars forever bought a metallic silver Accord and was hooked. I drove it and was hooked, too.

GM’s response to the Accord and successive waves of hot selling

offerings from Honda and later Toyota and Datsun (Nissan) was to

continue churning out formulaicly unattractive and uneconomical cars of

dubious quality. In fact, GM’s only direct response to the so-called Japanese Invasion was an abomination called the Chevette.

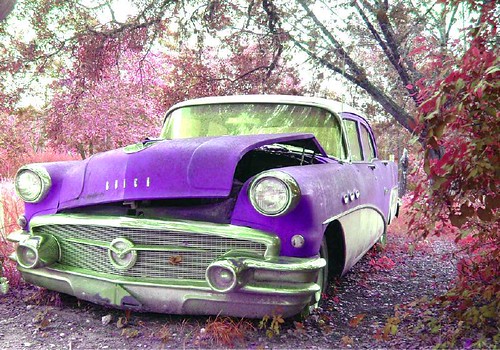

The General’s fortunes briefly improved after Rick Wagoner took over as CEO in 2000 and GM's share price soared to a record $90. (It is $37 today.) But

beneath the gloss the same fundamental problems persisted, eating into

the huge corporation like rust spreading through the underbody of a

Cadillac Coupe de Ville.

These problems included overcapacity

– too many assembly plants and not enough orders, sweetheart contracts with the

United Auto Workers union, purchasing foreign car companies and then

taking huge losses when GM couldn't make them work with their business

model. (What it did to Saab was unforgivable.)

But

the biggest problem was that Wagoner’s GM was coasting along with pretty much the

same tired product line as much of the rest of the automotive world was

stealing a march on it with attractive and innovative products.

One GM brand was virtually undistinguishable from another. Calls

to cut back on the duplication of models between brands and to even

fold the lesser selling brands largely went unheeded. Most ominously for GM, Japanese

automakers were opening U.S. plants and turning out cars (and later

small trucks) that were as well made as those at their vaunted home

plants while GM’s U.S. plants continued to produce poorly made vehicles.

In 1994, GM sold 35 percent of all cars sold in the U.S. Today

it sells 18 percent. In 2005, it suffered its biggest loss ($10.6

billion) since the Depression, and its failure to shake off its old ways

drove it to the verge of bankruptcy in 2008. Waggoner took a hike at

the behest of the Obama administration in 2009 as an unstated condition

for its taxpayer-assisted bailout of the automaker, Pontiac, Saturn and

Hummer joined Oldsmobile in going bye-bye, and while GM trails badly in hybrid technology, it

finally seemed to be shedding all that rust as it introduced spiffy new

models.

Yet it kept its old way of doing business.

In

a blistering report last month prompted by the deadly Chevy Cobalt

ignition switch problem that only scratched the surface of the GM

culture, former federal prosecutor Anton Valukas described what he

called the "GM nod." That's when managers nod in agreement about a

course of action but then do nothing. Then there is the "GM salute."

That's when managers, arms folded and pointed outward, indicate that the

problem at hand is someone else's responsibility.

* * * * *

In the wake of

the record recalls, which now total 54 in all, much has been made of the

fact that the turnaround of Ford, which alone among Big Three

automakers did not need a bailout, can be traced to Alan Mulally, who

became Ford's CEO in 2006 after a long career at Boeing, and not being a

car guy, let alone beholden to longtime Ford executives as Waggoner and

now Barra are, set out to change Ford's corporate culture.

Considering that Ford lost $12.7 billion in 2006 and made $8.6 billion

last year, it would seem that he succeeded.

To give Barra credit, she came up in the

product-development side of GM. Her father was a toolmaker at Pontiac

for 39 years. She seems to have cooperated fully with Valukas; it was

she who told him about the G.M. nod. Most importantly, she seems to

understand what is wrong with GM's deeply inbred culture, which punishes

whistle blowers rather than heed them.

But there is no indication that Barra knows how to change that

culture, let alone an arrogance that has survived GM's long slide from

being the world's largest automaker to its near-death experience and now

the stunning series of recalls, many of which would have never come to

light had it not been for the Cobalt crisis. Mulally's vision

eventually trickled down to middle managers. What is Barra's vision and

how is she going to make sure it trickles down?

Fifteen

GM employees have been dismissed for their roles in allowing the

original ignition defect to go unrepaired for more than a decade, while

regulators imposed a $35 million penalty for failing to report the

problem in a timely manner. A wrist slap, to be sure, and it is highly

unlikely there will be criminal prosecutions as a plan fashioned by

compensation expert Kenneth R. Feinberg to swiftly pay fatal accident

victims' families more than $1 million, and in some cases as much as $4

million, each goes into effect.

What makes Barra's job even

tougher is that a precipitous drop in sales might have a sobering

effect, but GM is selling cars like hotcakes despite the recalls, yet again confirming that P.T. Barnum was right.

GM registered a 12.6 percent increase in sales in May, significantly

outpacing Ford's 3 percent growth, and eeked out a 1 percent increase in

June as Ford sales fell 5 percent, while the many millions of

dollars that will be paid out will be written off as the price of doing

business.

Like the 9/11 and BP funds administered by Feinberg,

the GM fund is designed to keep victims

from filing lawsuits. They must be willing to waive the right to sue before they are paid. And those millions to be paid do not include punitive damages, so taken in the most uncharitable light, GM is getting away with murder.

Robert Stein was the longtime editor of Redbook in its heyday, publisher, media critic, journalism teacher and blogger, former chairman of the American Society of Magazine Editors, and author of Media Power: Who Is Shaping Your Picture of the World? He was a friend of the rich and famous, including Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy Onassis. And he was my friend.